Bone Music: The Fascinating Way X-Rays Were Used to Distribute Illegal Music in the Soviet Union

First discovered in 1895 by Wilhelm Conrad Rontgen, X-rays have since become one of the most vital diagnostic tools in medical imaging. The first clinical use of X-rays by physicians started the year after Rontgen’s discovery, and he later went on to earn a Nobel Prize in Physics.

But did you know, people used to use X-rays to listen to music?

Just a few decades ago, one of the biggest culture shifts was taking place in the world of music. When World War II ended and the Cold War began, the Soviet Union shut itself off from the Western world, banning all things considered traitorous. Almost everything Western was forbidden because the West had become the enemy, and our culture was considered harmful to the Soviet way of life. This was especially true when it came to music. Despite this, some clever fans were able to access the music of the West through an unconventional format: X-rays.

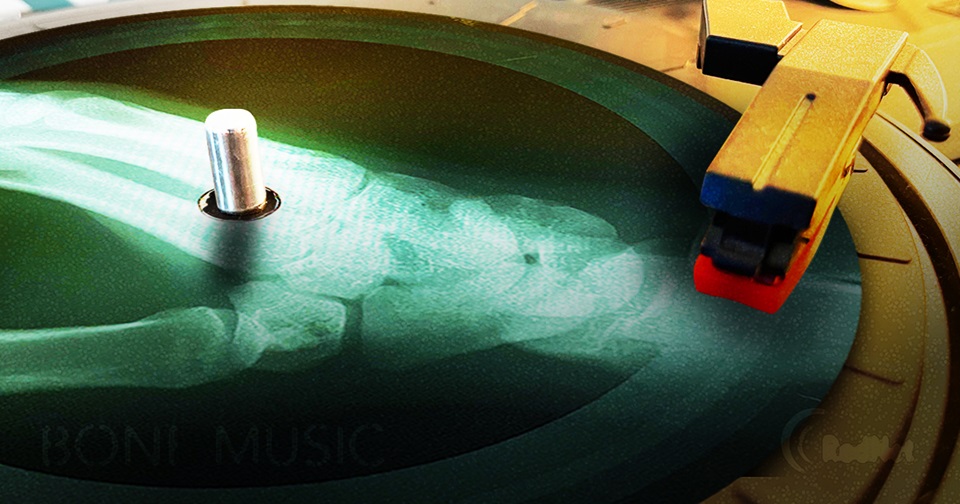

When Soviet soldiers returned from the war, they brought with them many trophies, one of which was a machine called a recording lathe. This machine allowed anyone to make grooves onto plastic and create their own records. From the late 1940’s to early 1960’s, however, this was easier said than done. The government controlled all aspects of creating records, so getting vinyl to press records was difficult. To get around this, bootleggers started using discarded X-rays from local hospitals. These X-rays were etched with all kinds of rock and jazz music, and were bought and sold in alleyways, parks, and on street corners, away from the prying eyes of Communist authorities. These records became known as “Ribs” and “Bones.”

An underground network of bone music distributors emerged, called the roentgenizdat (X-Ray Press), which were soon distributing millions of bootlegged records. It wasn’t long however, before Soviet officials caught on to these operations and the practice was made illegal in 1958. The government began hunting out distributors of bone music and confiscating X-ray records. In 1959, the largest roenrgenizdat ring was broken up, thus ending the short life of bone music.

English musician Stephen Coates from the band called The Real Tuesday Weld became fascinated with bone music when he came across an X-ray record at a flea market in Saint Petersburg. He was inspired to launch The X-Ray Audio Project, an initiative to provide information about roenrgenizdat recordings with visual images, audio recordings and interviews. This lead to his book, X-Ray Audio: The Strange Story of Soviet Music on the Bone, and later, a documentary for the BBC called Bone Music.

According to Coates, what’s especially fascinating about bone music, is not just the production of music onto X-rays, but “what people will do to hear music when there’s hardly any of it around.”

Today, you can still find some of these relics to purchase as collectors’ items, particularly on sites such as eBay. While we may not use X-rays for listening to the latest tunes, X-Rays have come a long way. In fact, 150-million X-rays are performed every year in the U.S alone, and each one helps doctors diagnose and treat their patients. X-Rays are also available in digital format today, which we use at our RadNet centers. This makes images even more enhanced and ultimately, makes the old film version used for bone music nearly obsolete.